I had the chance to interview Tim Heidecker on Riverside Chats about his latest turn in a multifaceted career to a live tour, but maybe not quite the way you'd expect. Half of his show has him in character as a bumbling, awkward comedian failing to connect with the audience. Then the rest of the show is genuine, authentic music written by Heidecker and performed with his Very Good Band. Below is our conversation (which we did before the start of the Screen Actors Guild strike and which has been edited for clarity) about artifice and authenticity, how he harnesses both, and the decision to bundle them in his Two Tims Tour, which you can see at The Admiral on August 23.

Tom Knoblauch: I'll start off with a little preface, which is I've been a fan for a long time, so I will do my best not to Chris Farley my way through this.

Tim Heidecker: Thank you. That's nice. Nice to hear.

Tom Knoblauch: So, Americans like to think of our signature archetype as this brave cowboy rebel, you know, forging a path of individualism and self-reliance. And maybe there was a time when that was a thing, but I've loved how so much of your career is focused instead on what I think is a much more prevalent archetype for us, which is the image-obsessed grifter.

Tim Heidecker: Uh huh.

Tom Knoblauch: These grifters, oftentimes when they're portrayed in like an Oscar-winning movie, they're the noble hustler, or at least they have some kind of emotionally complex genius to them. And for you, as you’re playing yourself as a grifter character, you lean into the pathetic and shallow elements, even when there's some success that's achieved. So I wonder, how did you come across this type of character, the grifter? How did you first become aware of them in society?

Tim Heidecker: Oh, that's a great question. I don't think I've ever really been asked it that way. I grew up watching infomercials and televangelists, and politicians and a whole generation of a style of presentation that was, you know, nakedly exploitative, I think, and obvious to me and my, my dad, particularly, who had and still does have a very skeptical, almost verging into cynical perspective on just about everything. So I think I was just kind of raised with a very attuned sense of hucksterism and flimflammery. I think it starts there, and then sort of the meta, postmodern turn, maybe starting with David Byrne and the Talking Heads and that kind of idea that all of this is phony.

And anytime you're presenting yourself as an entertainer or trying to impress people, there's a sort of plastic quality to that, an inauthentic quality, and it's funny and interesting to be over the top with it, I guess. And so even with Tim & Eric stuff, there's this sort of ironic level of presentation to everything we do that's usually over the top or overly insincere and just making fun of the idea of entertainment itself.

Tom Knoblauch: Your dad worked at a car dealership, right?

Tim Heidecker: He did, yes.

Tom Knoblauch: Did you learn some tricks from the car trade that spilled over into this world?

Tim Heidecker: I think a little more of just the personality of a car salesman. There were a there was a lot of characters there that a lot of just ridiculous personas that you could draw from that my dad wasn't really like. And I think my dad didn't associate himself with them, that he always felt out of place in that world. He didn't necessarily like it. It was kind of thrust on him. But he saw this silliness of the different techniques some of these old-timers would use to try to sell a car.

Tom Knoblauch: I love Mister America, where you bring all of this to a very specific and pointed head, a campaign movie where your fictionalized self is running for District Attorney of San Bernardino, despite not living there or having any kind of law-related credentials. And I remember watching that—I mean, it came out in this time where there was a lot of chaos and the beginning of our era of a lot of uncertainty around the American political system—and specifically, I found a kind of catharsis when your character doesn't win in the end.

Tim Heidecker: Right.

Tom Knoblauch: It never made sense that he could win, but America had conditioned me to sort of expect that maybe this guy might fail his way all the way to the top. Was any of that on your mind?

Tim Heidecker: Yeah, I think we always try to keep the satire we do in whatever it is we're working on grounded in some level of believability or reality. And it did seem a bridge too far to have some kind of success. I mean, there's another way to tell that story, where it's a darker version of America where he does win, and that almost felt too hard to swallow, too hard to believe and preachy, almost. So the satire was sort of secondary. The human pain of these characters is more interesting to us.

And there's satire in there and sort of a reflection of the current state of the world. But we're more interested in the pathetic human qualities of these characters and watching failure happen. And so having him win is never—I mean, it’s sort of like he's always winning, because he's not losing, you know?

Tom Knoblauch: Right.

Tim Heidecker: Like, he does lose that race. But he's still in the arena. That character doesn't get fully ruined ever. He always kind of comes back. So even in losing an election—it's a little bit like Trump—it's like, he lost it, but he's not going away.

Tom Knoblauch: He doesn't ever learn a lesson from any of it.

Tim Heidecker: Right. Yes, exactly.

Tom Knoblauch: I think in the difference between your Tim & Eric stuff when you're working with Eric Wareheim, and then when you're not, it seems like there's a little bit more of a pointed satire when you don't have Eric there. Whereas with Eric, it's a little bit more broadly absurd. Do you think that's fair?

Tim Heidecker: I do. I do. I think there's a lot of satire and parody in Tim & Eric, that is maybe more not as pointed and not as specific to politics. I mean, I think we definitely stayed away from that, intentionally. Not really out of any kind of fear of alienating people or anything, but more that we just felt that other people did it better. I think in Tim & Eric, there's a broad satire of capitalism and American consumerism and going back to infomercials and cheap crap that gets hoisted upon us. Foisted? Hoisted?

Tom Knoblauch: Hoisted, yeah.

Tim Heidecker: There's clearly, I think, a point of view about the world there that isn't that different from what I do without Eric. But at the time we definitely wanted to keep the show away from current events and try to hang on to a longer shelf life for it by not talking about what was happening in the world at that moment.

Tom Knoblauch: You were coming into the entertainment industry around the time when it was very popular to be doing current event shows, right? Like that was around the time that The Daily Show was getting really big.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah. And Colbert.

Tom Knoblauch: And so now it seems like there's a less of a clear idea of how you deal with politics in entertainment. I mean, there's a big question: did the Jon Stewart revolution really accomplish anything? It's almost like people are grappling with having to process our political system, which is absurd, through comedy, but it's not clear how to do that in a way that does anything other than maybe be snarky or maybe make a point. And we're in such a fractured world. How do you deal with politics in entertainment is a question that's only gotten murkier, right?

Tim Heidecker: Yeah, I mean, the only time I deal with it—I deal with it on Twitter, or I used to at least. I don't really engage there anymore—is on Office Hours, the live morning podcast that we do. It comes up and sometimes I get preachy. You know, it's a live show where I get to sort of be a little bit closer to myself and talk about what I care about.

But then there's just ridiculous, absurd things that happen every week that are fun to talk about with your friends. And that's the vibe it’s meant to be. Like, you know, if I was hanging out with my real friends, who are Doug [Lussenhop] and Vic [Berger], who I'm on the show with. Like, what would we talk about? And a lot of times you can't not talk about what Trump said or what gaff Biden made or something. So I don't like intentionally steer away from it. But, you know, it's definitely not the kind of show—there's a lot of these shows where it's guys on a microphone complaining about stuff. And that's not what we're trying to do. But I'm not going to ignore the absurdity of the moment to protect us from attacks from people.

We're definitely in a place where it's hard to satirize things. And I think the things we look to satirize are way more specific and maybe not apparent. So On Cinema, which I think is more what you’re thinking, is the show where we might find part of American culture that might not be obviously absurd at the moment but is veering towards absurdity. And in fact, I just came from a writing meeting with Eric Nortarnicola and Gregg [Turkington] about the next season. And I stumbled on some dark part of the internet that I don't know how many people are aware of. I mean, it's fairly popular. I don't want to say what it is. But I said, “This is something I want to drill into you guys.” And they're like, “Yeah, this is ridiculous. I can't believe this.” And maybe it won't seem all that ridiculous to other people, but it does to us.

Tom Knoblauch: In Nebraska, our PBS station would play [Roger] Ebert at midnight on Friday or Saturday. I would stay up to watch that. And I remember occasionally I'd be with friends, we'd be hanging out, and I'd say, “Oh, shut up. Let’s watch Ebert,” and they were probably wondering why they were friends with me.

Tim Heidecker: Just Ebert?

Tom Knoblauch: I was mainly watching when it was Ebert & Roeper. And then, I don't know, there would occasionally be guest hosts because Ebert had health issues. I think I just called it Ebert, maybe. And I just started off being a movie buff, and I was excited about the movies. And then YouTube opened up the archives. And you can see all this drama with him and [Gene] Siskel, and I realized that, while I did like the insights about movies, watching these two guys be hostile with each other is much more of the appeal at a certain point. And just the idea of two guys who don't really respect each other—or don't really want to be in a room together but have to be—is so fun. And I would guess that that's partially how On Cinema came about.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah, I guess so. I certainly grew up with those shows and thinking that they mattered for a little while. And then, you know, I remember this moment when Roger Ebert himself wrote a review for Tim & Eric's Billion Dollar Movie. And I suggest people go look it up because he hated it. And it might be one of the last reviews he ever wrote. There is a sense in the review that he's kind of given up on trying to figure out this movie. And there's almost a sense of like, “What am I doing? What have I done with my life?”

And it was weird because I had recently enjoyed him before that because he’d written this review of a movie that I'm gonna blank on right now. But you could probably remind me of what it is because it was Terrence Malick's last movie.

Tom Knoblauch: Tree of Life?

Tim Heidecker: Thank you, it’s Tree of Life. And I loved that movie, and I thought Roger Ebert wrote a really nice review of it and helped me understand why I loved it. So I do think there's value in writing about art, but then I read his review of our movie and was, you know, hurt by it. But then I talked to my dad—again going back to my dad being very skeptical and cynical of many things—and he couldn't believe that I cared.

He was like, “Who cares what he thinks? What does that have to do with anything?”

And that kind of brought me down to earth and reminded me that it is a little silly. And that maybe may have been in the back of my head as we went into doing On Cinema. But, you know, I just love Gregg, and I enjoy playing off other people. And I obviously have a different comedic relationship with Eric than I do with Gregg, but they both work. And I had John Early on Office Hours yesterday. And that's a different comic energy and relationship that has its own rules and everything. And it's just: I'm very grateful that I don't have to be this one kind of comedy guy. I can play in different ways with different people. And it's really just a joy.

Tom Knoblauch: You make me think about Ebert struggling with absurd humor. I think about that movie, Clifford—with Martin Short and Charles Grodin.

Tim Heidecker: Oh, yes.

Tom Knoblauch: And I think he gave it like half a star. And it's similar to your reaction, or what you were describing about him reacting [to Billion Dollar Movie], just kind of giving up, that when he watched Clifford, he sort of was like, “I don't know about humanity anymore.”

Tim Heidecker: Yeah. Yeah. Didn't seem like the most fun guy to hang out with, maybe.

Tom Knoblauch: Well, it's interesting. I mean, I think that's probably true of a lot of critics that there's something about absurdity and humor—if they can see it as being smart, it's like they can let themselves lock into it and accept it. And if it's very just goofy and silly or intentionally dumb, that there's something in them that feels like they can't totally validate it. And I don't really know why that would be.

Tim Heidecker: Bob Odenkirk was the guy that found Eric and me and was really our mentor for a long time, and when our stuff first came out, there was it was very polarizing, as it still is, but it was new to us. It was like, “Oh, wow, these people really have a visceral reaction to our work. And they're really mad about it.” And Bob's perspective was, “You know, this is very singular to comedy because I think when people don't get the joke, or they don't find something funny, they take personal offense to it. Often they're like, ‘This must mean the joke is on me.’”

And I haven't really felt that way. I mean, there's certain comedy I really don't like, of course, and we all have our preferences. But I think that's maybe where Ebert might fall into that category. A little bit of like, “If you're laughing at this and I'm not . . .” We've all had that feeling of being in a room where everyone's laughing and you're not, and there's a deep insecurity feeling going on there. So yeah.

I mean, he's dead, though, so who cares?

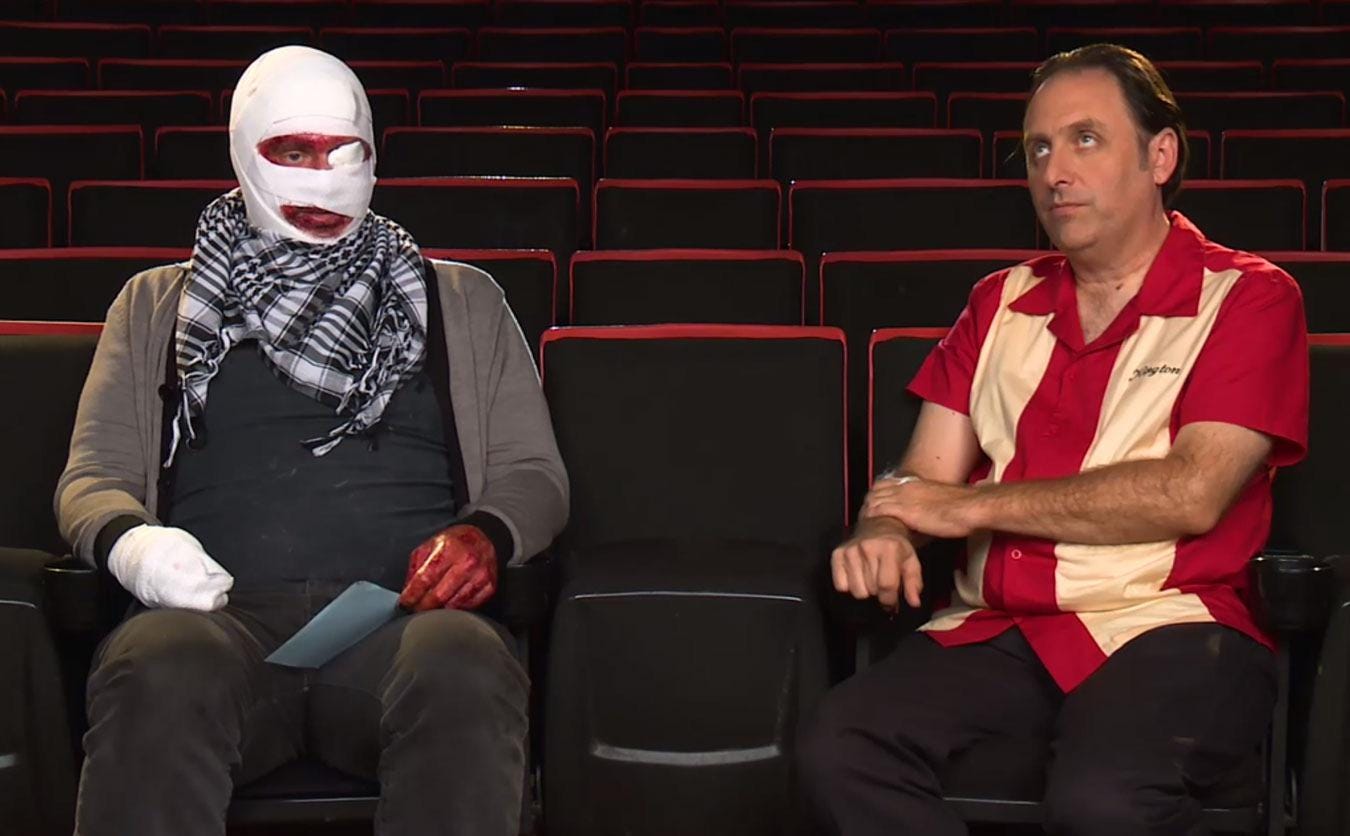

Tom Knoblauch: You've talked about how you like to work with people who bring out different elements in you, and you've done a lot of different types of media within entertainment, and The Two Tims is the name of your tour. The Tim Heidecker alter ego is very different from you. You're very self-aware, you have all these talents, you're able to branch off into different things. But then when you play this other version of yourself, who has your name, he's just the biggest buffoon imaginable. He's almost an impressively bad actor. He's on trial for murder sometimes.

Tim Heidecker: Right.

Tom Knoblauch: And one of my favorite things about the new seasons of On Cinema is how you'll find some new way to look as unflattering as possible.

Tim Heidecker: Yes.

Tom Knoblauch: So why create this fictional Tim Heidecker, who is named Tim Heidecker, instead of like an Alan Partridge alter ego?

Tim Heidecker: I think, in hindsight, it might have been a better idea to come up with a couple of different names for these people. But it is what it is. I come from the Andy Kaufman school of having intentional confusion and multiple personas and being interested in that idea of never really knowing where someone's coming from. And making that part of the journey of appreciating their work, I guess. Sounds quite public radio, the way I said it there.

So that's where it comes from; it's not that complicated. I guess for a while that was really the only way I presented myself, in various characters that just were under my name. Because there's also something—back to that sort of meta, postmodern, ironic idea of entertainment—in the idea that a phony character name is just another unnecessary step in the process. Eric and I began by having these personas of Tim and Eric, and they certainly weren't us at all, but it's almost too old-timey to have goofy character names, you know?

So it's all that and then, as I got older and hit my 40s and started being less interested in only existing in character form and finding social media and Office Hours and my music, it was like, “Oh, well I could sort of be closer to who I am.” But that becomes another character, almost.

Tom Knoblauch: I think it's interesting how you're merging artifice with authenticity in the new show. In The Two Tims you're going far into fake Tim but then bringing this very authentic, soulful musician at the same time.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah.

Tom Knoblauch: It's counterintuitive to put those together. How did you come to that idea?

Tim Heidecker: Well, I think there's a limit to our tolerance for irony and satire—I think there's an exhaustion point. I give a lot of credit to my audience, who I find generally smart and aware of what the joke is, what the joke is supposed to be, what's funny about it, and knowing that, like, you're, you're all adults, and you know that this isn't really me. And that I have other interests, and I have other ambitions. And you can like both of those things.

I wanted to do a tour of my comedy. I wanted to do a tour of my music. When you put a big tour together, it's a lot of work to get it together to a place where you can go off and do it, and it ends up eating up a lot of your year. And you have to really commit to it. You just really have to say, “Alright, I'm doing this,” and I have to decide to do it well in advance.

So I just thought, “Well, I can open up for myself and kind of satisfy these two parts of my brain.” And hopefully the audience's brain and making a night of laughter and tears—or not tears—well, there’s a couple of sad songs, I'll tell you. But it's it worked out really well. And I think there is this apprehension at first with the music because I'm educating my audience that not everything I do is going to be tongue-in-cheek. And that can be uncomfortable for the audience at first, but then the music is really good, the band is great.

There's a sense of, “Alright, this is just, this is a show, like any other show.” I don't make myself not funny for the second half of the show. And the music—I don't suddenly become a mopey indie rocker. I want to just make people feel relaxed. I have Vic Berger on stage with me. We're joking around.

What I'm learning from doing this is I'm trying to break the chains of genre a little bit and say, “Don't worry about what this is. Just try to take it for what it is and not worry about where you're going to file it on your bookshelf or in your record collection.” Like, it's just stuff. It's just stuff I'm making. And I get that. And I trust that you can receive it the way I want it to be received.

Tom Knoblauch: Was there an iteration of the comedy portion where it was more of the actual you—the self-aware you—as opposed to the character satirizing this wave of comics in the current political moment?

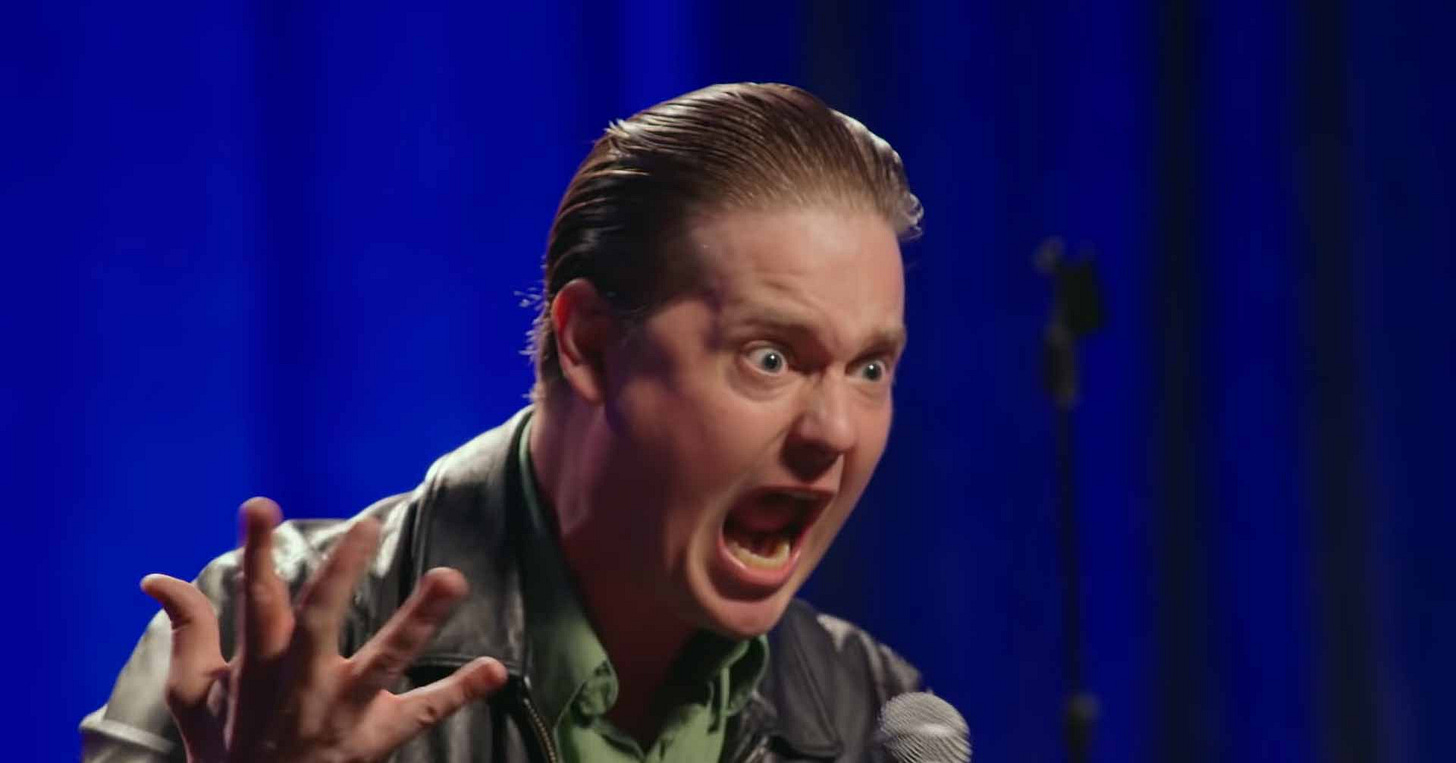

Tim Heidecker: I think if you look at the very beginning of that character—that’s on YouTube, you could see the first time I did it on my YouTube channel, buried deep down there—it's like it was done as a stunt. And it was done as kind of a reaction to bad open-mic comics that I would see. And it's way more me and way less secure, way less confident about the material and way more kind of stuttery and fumbling. And as I did it over the years, the character becomes way more cocky and confident. You know, strutting around like he thinks he's Jerry Seinfeld or is like a great comic.

So that's where the change is. And that's way more of an intentional character choice and probably informed by Trump and that kind of swagger. And that kind of idiotic confidence that he has on stage. So it's definitely far removed from me, but it's also very cathartic to do that character. It's very fun to be a total ass and abusive person on stage for 20 minutes, 30 minutes. So I get a lot of satisfaction out of doing it. But I would never act that way in my life in my real life to anybody.

Tom Knoblauch: Is there a desire to someday keep the kind of funny authenticity of the musical portion and then to present the standup part maybe closer to you on Office Hours?

Tim Heidecker: I've recently dipped my toes in that here in Los Angeles. There are a lot of friendly shows where I can kind of go up and do 10-20 minutes and try some stuff. And so the past, I don't know, a month or so I've done that a couple of times, where I didn't feel like getting into that character.

And doing that character is fairly limiting. There's only there's certain borders, and there's a structure to it. Same with like Tim & Eric stuff, or anything I do. Or in On Cinema, there's a world that where that character exists, and to go outside of it kind of ruins the character, is untrue to the character. There are things where I'm on Office Hours and I can do bad impressions or talk about The Beatles or talk about things that interest me outside of the things that would interest those characters.

And so I did it a few times. I mean, it's way more nerve-wracking to do that than to go up and intentionally bomb under the mask of a character in a costume, so it was a little intimidating. But then it was really fun. And it was like, “Oh, wait, this is a whole other thing I could do.” Which is exciting to me. And that's been my career, I think, getting to a place and not getting bored of something but feeling like its momentum is slowing and then there's something else that is exciting.

To try that might not work right away. I can work on and try and try to do better. And then I do that for a while, and then the momentum slows on that. So I'm constantly getting distracted by the shiny object over there and running towards it. And maybe that's a disastrous way to live. But it makes me excited to keep making things.

So who knows? This summer, it's “No More BS.” I know I'm on public radio.

Tom Knoblauch: We can bleep it if you want to say the whole word.

Tim Heidecker: It's fine. I like “BS.” It’s pathetic. But it would be fun to do a little tour where I can just try other things. I was watching Steve Martin from like his first stand up special and which is really great. It's on YouTube, but it's it's him at The Troubadour in Los Angeles and then maybe 100 people in the audience or something. And it reminded me of another way to present comedy that I hadn't really thought about in a while—and I'm not going to come out with a banjo or anything—but it's just being open to trying new things and pushing the limits of what I think I can do is always on the back of my mind, and I hope I keep doing that.

Tom Knoblauch: I remember watching the episode of Decker where you sing “Our Values Are Under Attack” and being impressed that even this bad actor version of you can actually carry a tune pretty well. And so then in On Cinema, you're repeatedly making these jokes about your version of yourself wanting to be this cool guy with the band and not doing it that well.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah.

Tom Knoblauch: Meanwhile the real you is doing it and doing it fairly seriously. And having a real craft, being able to sing, and without all the image stuff that fake you gets obsessed with that then tends to take him down. But I wonder: is it a difficult process for you to develop your voice as an actual authentic singer-songwriter instead of the characters or your comedy instincts spilling over?

Tim Heidecker: Yeah, it is. I mean it's another narrow lane that I have to keep in check. And there's a lot of failure in there, too. There's a lot of try and try and try again and write songs. When I was working on finishing a record right now, one of the songs was just too, I don't know, power ballad rock. Verging on Dekkar, which is the fake band in On Cinema. It's all editing. The stuff that that anybody ever sees is what I feel very confident to put out and I feel like this is what I was going for. And there's a lot of stuff that ends up on the cutting room floor.

I'm very self-conscious of not trying to be in that world, just trying to be myself, and not trying to put on an aspect of a rock singer, even though I can do that. You know, I can. I am a passable rock singer. I can do that thing. It's fun to do that thing. But when I'm singing a song that's coming from my heart, I try to just do the best I can. And the songs I write fall into this kind of Randy Newman, Warren Zevon-y kind of thing where, when I sing those kinds of songs, I try to sing like the way I sound—which I don't really like to listen to. I think it's a little too naked for me, personally, because we all know no one likes to hear their own voice.

Which is I why won't be listening to this interview.

Tom Knoblauch: I get that.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah.

Tom Knoblauch: It seems like a lot of the current project for you then is learning to be yourself, to be authentic, to be naked publicly—so to speak.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah. Yes.

Tom Knoblauch: Does that feel healthier to you? Because we live in a time where everyone is very obsessed with image. And I don't know if it's because you guys were starting off during maybe peak irony—and that maybe that is leveling off? Or is it more of a personal project for you?

Tim Heidecker: Yeah, first of all, I keep talking about irony. And it's a very broad word, but I think we all know what we mean. I do think it's kind of a young, younger man's game. And I mean, I will still have ideas that are satirical and comedic and meant to reflect how I see the world—I’ll still make comedy, to say it in a simpler way. But I don't want that to be all I'm about. I think that it becomes very narrow way to live. I can live my private life that way, too. But you just don't want to be just entirely detached and too cool for school and think everything is a big joke.

I say it on my show all the time: I love to laugh and I love to have fun. I love it and it's who I am—I'm not being very funny during our conversation—but it's almost it's like it's more work for me. And funny is very subjective, but my natural instinct is to at least try to be funny or, you know, play to the people I'm talking to in an amusing way but so it's just trying to balance that, I guess, and try not to let comedy be my entire identity.

Tom Knoblauch: When you have an idea or a feeling and you're trying to find the right medium to express it, there are things that comedy is probably the right venue for then there are ones where maybe a song is the only way for you to sort of scratch whatever itch is that you're having. So how do you decide what a song needs to be? What can you express through song that comedy can't get to?

Tim Heidecker: Oh, boy. I don't know. I think music, songs come from a more subliminal place. I mean, they both come from subliminal places. They're just different. I don't know if I have a great answer for you. I could bullshit through an answer.

Tom Knoblauch: You don’t have to.

Tim Heidecker: No, yeah, I don't have to. I just don't know if there is a great answer for it. I mean they both come out of nowhere. You know, I wish I had a formula for generating them. I think when an idea comes, it'll come as a song or a melody or a kind of song I want to write. And then I'll try to do the best version of that. I guess comedy might be a little more reactive to something I see or hear. But sometimes stuff comes up as I'm trying to go to sleep at night, and I think of an angle on something and try my best to capture it the best way I can and see it through.

Tom Knoblauch: Let’s use one of your songs, something like “Fear of death is keeping me alive”—is that a sentiment that can work in comedy? Or is it always going to end up kind of mocking and harder to reach the emotion of that feeling if you were to do it through sketch or drama in some way?

Tim Heidecker: Well, that sentiment, that the fear of death is keeping me alive, is a joke, essentially. That does seem kind of like an old-timey joke, a paradoxical way of looking at why you live while you're alive. And it can be treated that way in the song, but it's also a real feeling. Death is a subject that, as humans, we're consumed by. And in On Cinema, but in Tim & Eric, too, there's constant playing with the idea of death. And I don't really know why, but I think there's this idea that we play with these dark ideas to process them and understand them and make them not as scary as they can tend to be.

There's a fundamental absurdity to life because what awaits us is death. And if you're not a particularly religious person or faith-driven person, there's kind of a dark absurdity to the whole thing, right? So I think that just naturally filters into a lot of the stuff we do, whether it's music or comedy. But I don't think drama works because then it just becomes too serious, gets treated too seriously. More seriously than the subject deserves.

Tom Knoblauch: But it's the most serious subject.

Tim Heidecker: That's what's absurd about it.

Tom Knoblauch: So do you have an aversion to more serious art, then, as your personal way of expressing a lot of this—as opposed to comedy or music that can have that fun or sometimes the comedic element?

Tim Heidecker: I won't say I have an aversion. I almost prefer it from an entertainment perspective. I prefer a good drama more than what passes for comedies these days. I think it's easier to make a good drama than good comedy, maybe. But yeah, I mean, that goes back to the fact that I don't want to be mired in, drowning in irony and detachment. I want to be able to enjoy real, human experiences and watch real, human acts.

Like everybody else, I get wrapped up in my stories on my TV and find it a tremendous diversion from thinking about the absurdity of the death that awaits us. It's great, you know? It's just nice ways to spend time. I like watching baseball for the same reason. So we're getting into some deep dark psychological stuff here.

Tom Knoblauch: Well, that's that's what public radio is at its best, right?

Tim Heidecker: Yeah.

Tom Knoblauch: Essentially what you're saying is: because the natural world actually is absurd, absurdism is a more honest way of expressing how we feel and how we live.

Tim Heidecker: Right. Yeah. I just saw this quote from David Lynch that says, “I don't understand why people insist on art making sense, while at the same time they accept that the world doesn't make sense.” It's a better reflection of the real, the actual world when we present absurdity, but it's comforting and distracting and quite lovely to watch stories that present a world that makes sense—or at least people that make sense and find resolution and resolve.

I had this dumb idea, and I'm sure I'll never do anything with it, but it was the kind of idea that I would send Nathan Fielder. I was watching the show about a hijack. It's called Hijack. It's a thriller. Idris Elba. And the plane gets hijacked. And you know what you're gonna get. And that's why you watch it, because you're watching a show about a plane getting hijacked and seeing how they're gonna get out of it. And I was like, “It'd be interesting to watch a show where nothing happens, but it's treated the same way as that show.” It's literally a show about a flight from San Francisco to Boston. And there's a dramatic tension throughout this flight, but you're really just watching a five-hour flight. Just like jumping around to different interactions and the flight attendants coming down. I was like, “I wonder if I would watch that show.”

Nothing's really happening. But it's fun to watch people act. And it's fun to see what it's like inside of a plane. And I don't know where that's going. But there's something kind of just diverting and relaxing and enjoyable about just watching something you understand. And I don't know if I need to know what's going to happen to this hijacked plane. You know what I mean?

Tom Knoblauch: I think a lot of slow cinema, arthouse cinema has been trying to do something along those lines for a century, really.

Tim Heidecker: Yeah.

Tom Knoblauch: What you often find is people really don't want to watch it because they need some kind of genre construct or it needs to be funny or something like that.

Tim Heidecker: Right. And so this idea is that I would want to do it with Nathan because I think it would be funny to present it as if it's genre but then it’s nothing. The good stuff never really ever happens. The plane lands safely and people get off and get their luggage.

Tom Knoblauch: Sounds like the kind of thing Ebert, if he were still here, would again not particularly appreciate.

Tim Heidecker: Oh, he would be very incensed by the whole thing.

Tom Knoblauch: Well, you've done some work in genre—like Bedtime Stories plays with some of the horror tropes, and I love your part in Us. Quick aside: that noise you make in Us—that little roar noise—did you come up with that?

Tim Heidecker: Yeah, I think so. I think I went in there with an open mind. And Jordan [Peele] had an open mind and we just were figuring it out and trying stuff and he asked for some kind of animal guttural noise. I think in all these, he has a lot of ideas, but he's also like, “I don't know, like, what do you think? What would he do? What would this thing be?” And I'm just winging it, you know? I'm trying to entertain him and then try stuff and I made that sound. And he was like, “Yeah, let's try that.”

Tom Knoblauch: It's seared into my brain, that little sound. But anyway, genre seems like something that you do play with occasionally, adopting these more dramatic genre conceits. Is that something are you planning to continue to experiment with in those different directions? I know you've got the podcast, you got comedy, you've got music. Is there a next on the horizon? Or are you figuring out the current phase as it exists?

Tim Heidecker: Eric and I have started a couple movie ideas. Or at least that's what we want to do. We say, “Let's let's try to make another movie. Let's try to approach it differently than the last one, and maybe grounded more or make in a genre.” You know, everyone writes us and says, “We'd love to see you make a horror movie.” I'm not a big horror movie fan, but I think we could make something special, closer to the Lynch world, the Ari Aster world, than like a gore-fest.

So, yeah, I mean, I like making stuff, I like making stuff with Eric, and I like trying to solve those problems. But I’m at this place where I've made a lot of stuff, we've made a lot of stuff. And sometimes it's good to have some time to separate from that, you know? Just to not rush into something. And so we're just not rushing into what the next thing we want to do is, letting it kind of come to us organically. Which sounds a little bit like a procrastination excuse from doing work, but we are chipping away at it. And then it will just have to be like, “Alright, let's just do something, see what it is, if it's working or not.” Because you can overthink a lot of this stuff.

And I think part of our early career was very much based on not overthinking and not trying to figure out what the perfect thing to do is and just going out and doing stuff and learning by doing. The pandemic and the lockdown and everything, I think we're still in the hangover from that, you know? And it's hard to figure out what you want to do and do it. And hopefully that we're coming out of that now. I don't know if I'm the only one that feels this, but I think I'm not.

Tom Knoblauch: No, no, I think a lot of people feel that way. But it's tough to say you're procrastinating when you've got the weekly show . . .

Tim Heidecker: I know.

Tom Knoblauch . . . you're on tour . . .

Tim Heidecker: Yeah.

Tom Knoblauch: . . . and every few months you pop up on stuff like I Think You Should Leave and whatever else.

Tim Heidecker: The perception is I'm very busy. The reality is I’m more like Brian Wilson, bedridden in the 70s, half the time.